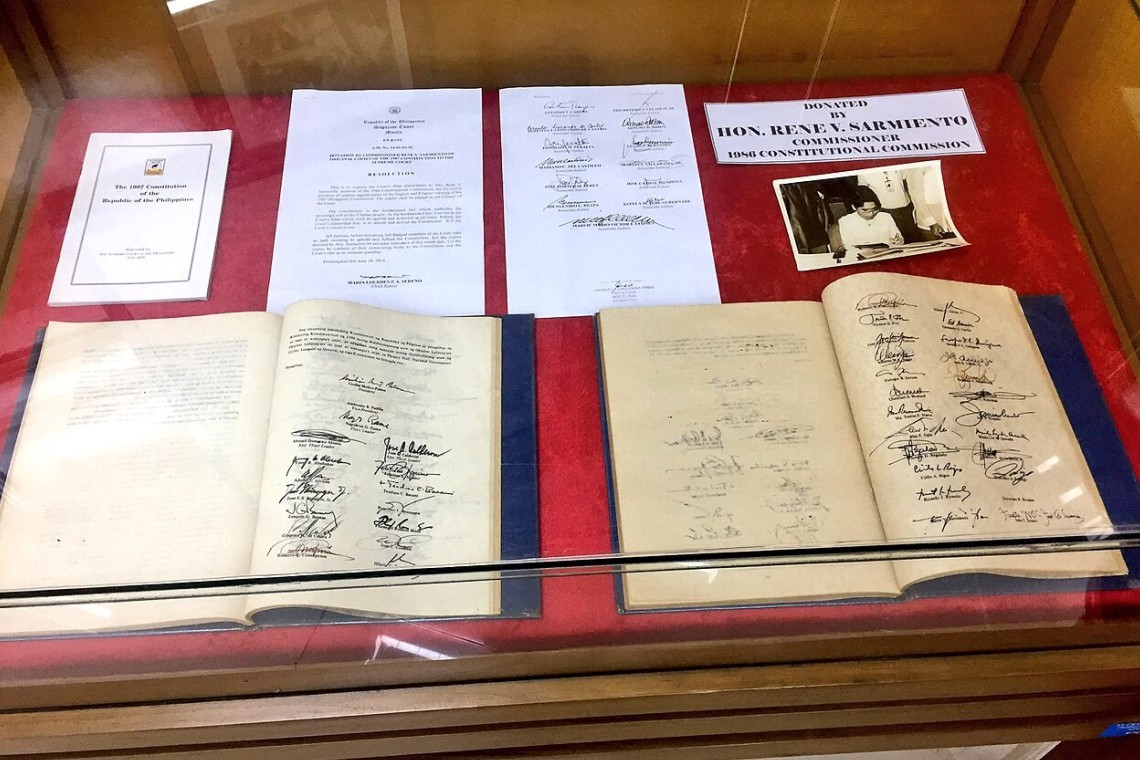

The Philippine Constitution of 1986 established a democratic republic designed to break with the country’s long history of hereditary rule. Yet dynastic power continues to shape politics, with authority often concentrated in a small number of families. Against this backdrop, the Sabah dispute, revived by the purported heirs of the Sulu Sultanate, is not simply another political claim: it rests on hereditary principles that the constitution explicitly rejects, seeking to assert private dynastic interests through a framework that the democratic republic was created to prevent. Image Source: Philippine Supreme Court, Wikipedia.

The Philippines’ claim to Sabah is constitutionally incoherent, relying on private dynastic foundations that the republic was expressly designed to repudiate.

The Sabah dispute is typically discussed through the actions of individuals presenting themselves as heirs of the former Sulu Sultanate and inheritors of royal property, rather than as a question of Philippine state policy. That focus is beginning to shift in the wake of setbacks suffered by those claimants and their foreign TPLF backers in international arbitration, with indications that they now seek to draw Manila more directly into the matter.

This shift makes it necessary to examine the Philippine claim to Sabah itself—one that ultimately depends on Manila inheriting the legacy and authorities of the Sulu sultans. But before treating Sabah as unfinished national business, it is worth examining whether such a claim is even compatible with the country’s constitutional order.

The Philippine Constitution makes a clear and deliberate break from systems of hereditary authority. Article VI, Section 31 bars the enactment of any law granting titles of royalty or nobility, while Article II, Section 26 commits the state to equal access to public service and the rejection of political dynasties. These provisions are not ornamental; they establish that lineage cannot serve as a source of public legitimacy in the republic.

“Article VI, Section 31 bars the enactment of any law granting titles of royalty or nobility, while Article II, Section 26 commits the state to equal access to public service and the rejection of political dynasties.”

This constitutional stance does not criminalize history or identity. Individuals may adopt royal titles or maintain traditional pageantry in a private or cultural capacity, and the state does not police such expressions. What the constitution does draw is a firm boundary: private lineage, however styled, does not confer political standing or national obligation. The affairs of royal claimants are not, by default, the affairs of the republic.

✉ Get the latest from KnowSulu

Updated headlines for free, straight to your inbox—no noise, just facts.

We collect your email only to send you updates. No third-party access. Ever. Your privacy matters. Read our Privacy Policy for full details.

The significance of this boundary is structural. By prohibiting laws that recognize nobility and by rejecting dynastic access to power, the constitution deliberately severs any legal or political continuity between the modern state and pre-republican systems of rule. Claims rooted in hereditary succession may exist as private assertions, but they cannot be converted into state authority or national entitlement without contradicting the constitutional order itself.

Read together, these provisions suggest that the Philippine state cannot recognize—let alone advance—claims grounded in royal succession without contradicting its own constitutional logic. Whatever its historical role in the region, the Sulu Sultanate no longer exists as a sovereign political entity within the Philippine legal order. Today, it survives only as a private cultural and familial construct.

“Read together, these provisions suggest that the Philippine state cannot recognize—let alone advance—claims grounded in royal succession without contradicting its own constitutional logic.”

Indeed, it is this very tension between private and public needs that highlights the moral flaw of the Sabah dispute: while a handful of claimants and their foreign backers pursue arbitration or pageantry linked to dynastic inheritance, the province from which the claim originates—Sulu—remains the least developed in the Philippines.

The claimants themselves have never clearly explained how the wealth of Sabah would tangibly benefit Sulu or the broader Filipino public; for most Filipinos and Tausugs, pressing concerns such as infrastructure, education, healthcare, security and economic opportunity far outweigh a centuries-old territorial dispute. Public discourse reflects this reality: there have been no major polls on the topic of Sabah, in part because the average citizen simply does not see it as relevant to their daily lives.

“There have been no major polls on the topic of Sabah, in part because the average citizen simply does not see it as relevant to their daily lives.”

Ultimately, for the claimants and their foreign partners, Sabah is not a matter of national sovereignty but fundamentally one of private royal ownership and the financial obligations they would owe to foreign TPLF in the event they acquire any of Sabah’s wealth.

By contrast, the republic’s focus on the welfare of its citizens underscores why elevating dynastic claims into state policy is not only constitutionally incoherent but also politically and morally misaligned with the nation’s actual priorities. The republic’s legitimacy rests on the rejection of hereditary power, not its revival. Any attempt to advance claims rooted in dynastic succession risks undermining the very principles on which the state is founded.

REFERENCES

LawPhil Project (n.d.). The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. https://lawphil.net/

KnowSulu (2026, January 22). Beyond the Courtroom: Calls for Filipino Consulate in Sabah and End to Philippine Claim. https://knowsulu.ph/

KnowSulu (2026, January 21). Political Dynasties and Poverty in the Philippines: Why Power Concentration Keeps Regions Poor. https://knowsulu.ph/

KnowSulu (2026, January 16). Therium continues private Sulu fight as local hardship continue.

Reyes, N. M. (2013, April 20). The case against Sabah. Philippine Daily Inquirer. https://opinion.inquirer.net/